Health Bulletin-October 2021

The Epidemic of Cardiovascular Disease Among South Asians: A Call To Urgent Action!

Much of our understanding of the risk-factors for cardiovascular disease (CVD) comes from the Framingham heart studies (FHS) done in the latter half of the twentieth century. Knowledge gained from these studies has been the backbone for cardiovascular risk estimation and has informed decisions on cardiovascular risk mitigation strategies such as identifying patients likely to benefit from some medications etc. In spite of many seminal contributions to cardiovascular disease (CVD) prevention, a major drawback of the Framingham studies is the lack of diversity as the early cohorts were exclusively Caucasian. Several more recent studies such as the Dallas Heart study, Multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis and the Omni cohort of the FHS have filled this gap and expanded our knowledge of CVD risk factors and progression among African Americans, Hispanics and Asian Americans.

South Asians are known to have a high cardiovascular risk with 1.5-2 times greater prevalence and 35% excess odds of incident of coronary artery disease (CAD) compared to age and sex matched Caucasians. They account for 25% of world population but close to 50% of CVD deaths worldwide. Furthermore, in the Interheart study, South Asians had the first myocardial infarction (MI) 6-10 years earlier than Caucasians. Notably, while the rate of CVD in most immigrant populations tends to blend with the rate of the adopted country over successive generations, South Asians seem to be an exception and tend to have persistently higher rates. Despite this, South Asians remain largely underrepresented in cardiovascular trials and are frequently aggregated with other Asian Americans who are racially and ethnically distinct. Recent studies such as the Mediators of Atherosclerosis in South Asians Living in America (MASALA) study and the Canadian Study of Health Assessment and Risk in Ethnic groups (SHARE) registry have explored CVD risk factors, progression and outcomes among South Asians in North America and have brought into focus the growing burden of CVD among South Asians.

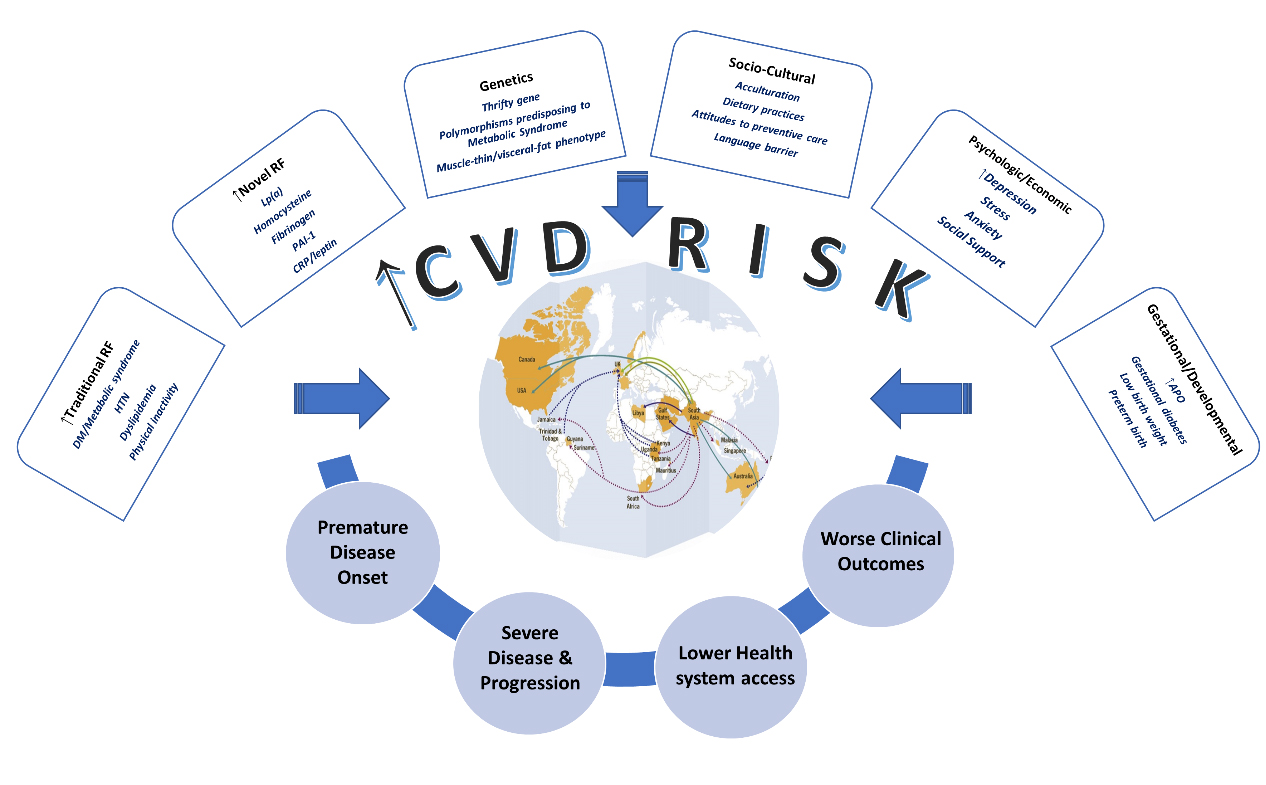

Several potential reasons for this excess risk in South Asians exist (Figure 1). First, the burden of a number of traditional risk factors is higher in South Asians. In one large analysis, South Asians had a 2-4-fold greater prevalence of diabetes and metabolic syndrome. In addition, hypertension, dyslipidemia and physical inactivity were more common while smoking was much less common among South Asians in the USA. More importantly, abdominal obesity is highly prevalent and at any given body mass index, South Asians have a higher body fat compared to Caucasians. In addition to the higher burden of traditional risk factors, novel risk markers such as lipoprotein (a), prothrombotic factors such as plasminogen activator inhibitor-1, fibrinogen, homocysteine and proinflammatory markers such as C-reactive protein are noted to be higher in South Asians compared to Caucasians. Acculturation and consequent Western diet may further increase risk of metabolic disease. While South Asian immigrants to USA tend to have higher educational attainment and better economic status compared to those living in their native countries, they may more often face language and social barriers. Furthermore, it should also be noted that South Asians themselves are a diverse group: while Indian Americans tend to have much higher income compared to average American household, other groups like Burmese Americans are economically disadvantaged. Finally, a number of emerging risk factors that increase risk for CVD such as chronic kidney disease, adverse pregnancy and developmental outcomes have been shown to be more prevalent in South Asians compared to Caucasians.

Beyond the presence of high-risk factor burden, it is known that South Asians tend to have inferior control of risk factors (worse hemoglobin A1c, suboptimal lipids) and a more aggressive disease course compared to other races. This could be due to biologic, or non-biologic (dietary or socio-cultural) reasons. Furthermore, they have more extensive pre- clinical disease as assessed by coronary calcium score or carotid intimal media thickness and more severe and extensive clinical disease at diagnosis such as multi vessel CAD etc. Notably, South Asians are more likely to present late after an MI, defer or avoid preventive care visits which can potentially contribute to worse outcomes. Despite this, the outcomes of South Asians with myocardial infarction or undergoing percutaneous intervention appear comparable to non- Hispanic Whites (recurrent MI and mortality) which could be related to their younger age and lower risk of non-cardiac mortality such as cancer. In contrast, South Asians have been shown to have worse outcomes following coronary artery bypass graft surgery (CABG). It is important to note that despite comparable outcomes after an MI, the proportional mortality rate from ischemic heart disease is highest among Asian Indians compared to non-Hispanic Whites and other Asians. As a consequence of premature disease, Asian Indian men and women on average lose 17 and 13 years of productive life due to ischemic heart disease compared to 14 and 12 years respectively in their White counterparts.

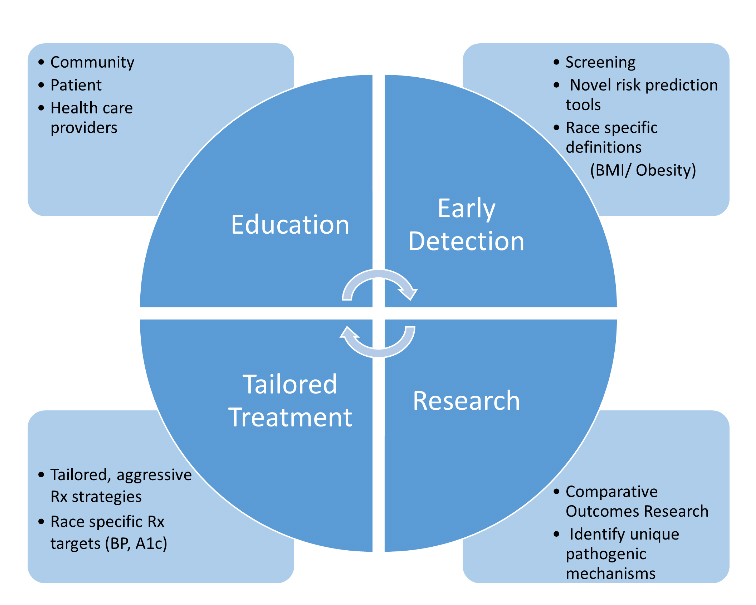

In summary, South Asians are the fasted growing ethnic/racial group in USA with a current population of 5 million and an expected population of 34 million by 2050. Given the magnitude of CVD burden among South Asians and the unique biologic and socio-cultural challenges, a multipronged and tailored strategy aimed at decreasing CVD burden, improving outcomes and decreasing CVD morbidity in this population is urgently needed (Figure 2). Patient and community education to increase awareness of the increased risk of CVD, health care provider education regarding the mechanisms underlying this excess risk, inadequacy of current risk prediction tools and biologic/non biologic factors impacting CVD outcomes of South Asians is of foremost importance. Further research on mechanisms of excess risk, development and validation of novel risk prediction tools specific for South Asians and tailored treatment interventions that account for the biologic and unique cultural aspects of South Asians is urgently necessary. Hopefully, these advances will not only help the millions of South Asians living in the USA and North America but can serve as template and positively impact the cardiovascular health of the billions of South Asians living in their home countries.

ACRONYMS

MI: Myocardial infarction

CVD: Cardiovascular disease

CAD: Coronary artery disease

CKD: Chronic kidney disease

PAI: Plasminogen activator inhibitor

HTN: Hypertension

APO: adverse pregnancy outcomes

CRP:C-reactive protein

Lp(a): Lipoprotein (a)

FHS: Framingham Heart study

FRS: Framingham risk score

Key References

Volgman AS, Palaniappan LS, Aggarwal NT, Gupta M, Khandelwal A, Krishnan AV, Lichtman JH, Mehta LS, Patel HN, Shah KS, Shah SH, Watson KE; American Heart Association Council on Epidemiology and Prevention; Cardiovascular Disease and Stroke in Women and Special Populations Committee of the Council on Clinical Cardiology; Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing; Council on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research; and Stroke Council. Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease in South Asians in the United States: Epidemiology, Risk Factors, and Treatments: A Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2018 Jul 3;138(1): e1-e34.

Fernando E, Razak F, Lear SA, Anand SS. Cardiovascular Disease in South Asian Migrants. Can J Cardiol. 2015 Sep;31(9):1139-50.

Author information

Venkata Mahesh Alla MD, FACC, FASE

Associate Professor of Medicine

Division of Cardiology

Creighton University School of Medicine

Omaha, Nebraska

Coordinated By

Sujeeth R. Punnam, MD

Chair, ATA Health Committee

(Dr. Sujeeth R. Punnam is a cardiologist in Stockton, California and is affiliated with multiple hospitals in the area, including Dameron Hospital and St. Joseph's Medical Center-Stockton. He received his medical degree from Kakatiya Medical College NTR and has been in practice for more than 20 years.)

Join our

Join our